Nestled along the Mississippi River, just north of Alton, Illinois, looms a striking image painted on the limestone bluffs: a fearsome creature with wings, horns, scales, and a serpentine tail. This is the Piasa Bird, a legendary figure whose story has captivated generations, blending Native American mythology with local pride. Its name, derived from the Illiniwek language meaning “the bird that devours men,” evokes a chilling yet fascinating narrative that has left an indelible mark on the region’s history, culture, and identity.

The Legend in Full

The most widely known version of the Piasa Bird legend comes from an 1836 account by John Russell, a professor from Bluffdale, Illinois. According to Russell, long before European settlers arrived, the Illini tribes lived in terror of a monstrous bird that soared above the Mississippi River Valley. This creature, described as a hybrid of bird and dragon, was said to be enormous, capable of snatching full-grown deer in its talons. But its appetite soon turned to human flesh, devastating entire villages as it swooped down to carry off warriors and children alike. Its lair, rumored to be a cave along the bluffs, was filled with the bones of its victims, a grim testament to its reign of terror.

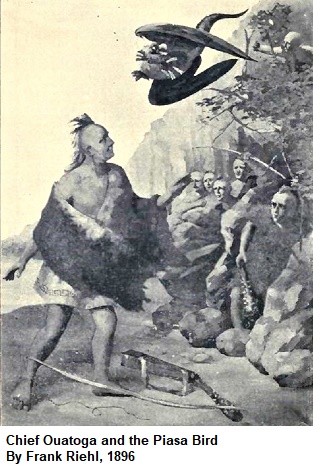

The Illiniwek, a confederation of tribes including the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Peoria, and others, struggled against this beast for years. Their arrows and spears proved futile against its scales and strength. Desperate, a courageous chief named Ouatoga devised a plan inspired by a vision from the Great Spirit. After fasting and praying in solitude, Ouatoga dreamed of a strategy: he would offer himself as bait to lure the Piasa into an ambush. Selecting twenty of his finest warriors, each armed with bows and poisoned arrows, he positioned them in hiding along the bluffs. Standing alone in an open clearing, Ouatoga chanted a warrior’s death song, drawing the creature’s attention. As the Piasa descended, its red eyes gleaming and claws outstretched, the hidden warriors unleashed their arrows. Struck beneath its wings, its only vulnerable spot, the beast let out a piercing scream and plummeted into the Mississippi River, vanquished at last. In gratitude, the tribe immortalized the event by painting the creature’s image on the bluff, a symbol of their triumph over fear.

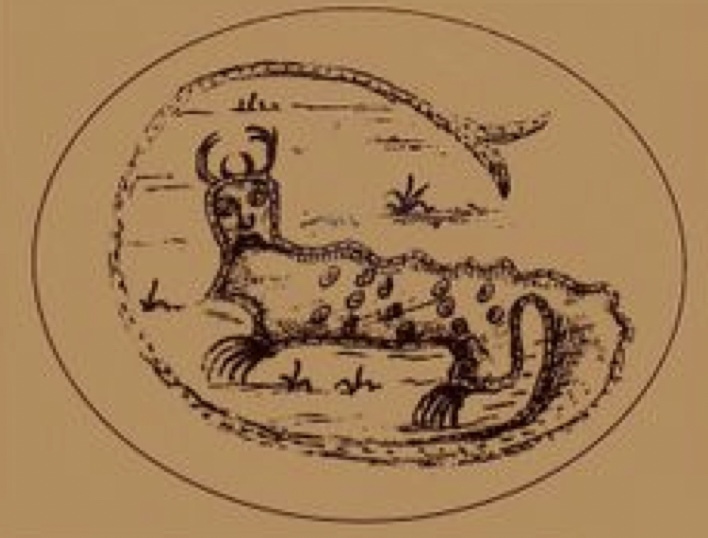

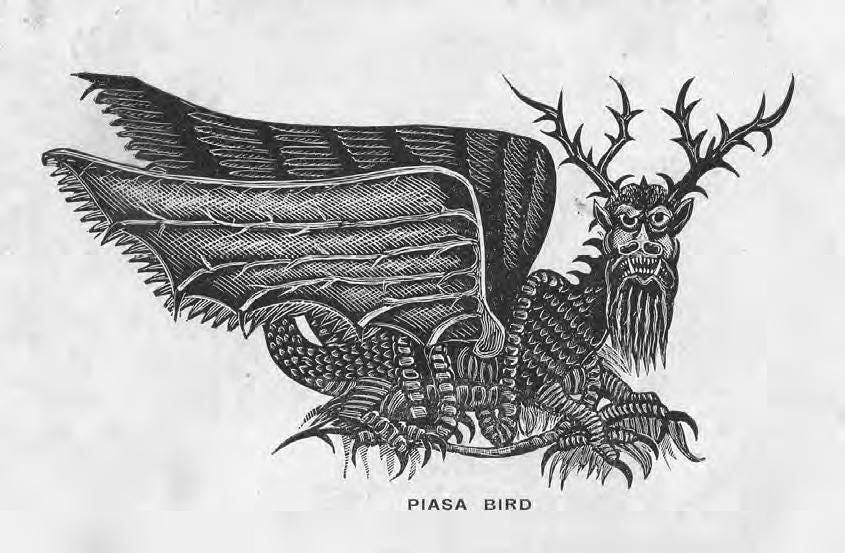

Yet, this dramatic tale is not without controversy. Late in life, Russell admitted to embellishing the story, casting doubt on its authenticity as a genuine Native American legend. Scholars suggest the Piasa may instead be linked to broader Mississippian culture motifs, such as the “underwater panther” or thunderbird, powerful spiritual beings tied to the cosmos rather than a literal monster. Father Jacques Marquette, who first documented the bluff painting in 1673 during his journey with Louis Jolliet, described two “painted monsters” with no mention of a battle. His account, depicting a creature “as large as a calf” with deer-like horns, red eyes, a bearded face, scales, and a long tail, offers a more grounded glimpse of the original pictograph, hinting at a symbolic rather than historical narrative.

Historical Context and the Illiniwek Tribes

The Piasa’s origins likely stretch back to the Mississippian period (AD 1000 to 1500), a time when the great city of Cahokia thrived near present-day St. Louis. With a population of 20,000 at its peak, Cahokia was a hub of trade, culture, and spirituality, its influence reaching the Alton area. The Illiniwek, descendants of this legacy, inhabited the Mississippi River Valley when Europeans arrived. Comprising twelve to thirteen tribes, they numbered around 10,000 before contact, but disease and conflict reduced their ranks to just five surviving groups: the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Peoria, and Tamaroa.

The bluff painting Marquette encountered may have served as a territorial marker or spiritual warning, reflecting the Illiniwek’s belief in a three-tiered cosmos: Upper World, This World, and Underworld. The Piasa’s features, wings, a spotted body, and a fish-like tail, could symbolize a being that bridged these realms, embodying both danger and power. Illini canoeists reportedly feared the image, leaving offerings to appease its spirit as they navigated the river’s treacherous rapids. Over time, this reverence evolved into a ritual of defiance, with warriors firing arrows or bullets at the painting as a show of courage, a practice noted into the 19th century.

Defeat or Mythical Persistence?

Whether the Piasa was truly “defeated” depends on which version of the story one accepts. Russell’s tale of Ouatoga’s victory is a gripping climax, but its fictional roots suggest the creature’s demise was more literary than literal. Archaeological evidence offers no trace of a giant bird, and the original pictograph, carved and painted on lithographic limestone, was destroyed by quarrying in the late 1870s. Some speculate the Piasa was a cultural memory of prehistoric creatures like pterodactyls, while others tie it to the thunderbird, a widespread Native American symbol of power and protection. In truth, the Piasa’s “defeat” may lie in its transformation from a feared entity to a celebrated icon, its menace tamed by time and storytelling.

Representation on the Bluffs

The Piasa’s image has been a fixture on the Alton bluffs for centuries, though not without interruption. Marquette’s 1673 sighting marked its first European record, but by the 19th century, the original artwork had faded or been obliterated. Efforts to preserve it began in the 1920s, when locals repainted the creature based on sketches and lithographs. These attempts faced challenges; the limestone’s crumbly nature caused paint to fade, and road construction destroyed earlier renditions. In 1984, a 9,000-pound steel sculpture was bolted to the bluff, only to rust and be removed by 1995. Today, it stands at Southwestern High School’s football field, a gift to the Piasa Birds mascot. The current bluff painting, completed in 1998 by the American Legends Society, spans 48 by 22 feet, its vibrant red, green, and yellow hues visible along the Great River Road. Regular touch-ups keep it alive, a testament to Alton’s dedication to its legend.

A Lasting Legacy

The Piasa’s influence extends beyond the bluffs, embedding itself in the region’s identity. Piasa Township, a small community near the high school, bears its name, as do streets, businesses, and neighborhoods. Southwestern High School in Piasa proudly adopted the Piasa Bird as its mascot, its fierce visage inspiring sports teams and fostering a sense of local pride. For Alton and its surroundings, the creature is more than a myth; it’s a symbol of resilience, a bridge between past and present.

As we stand before the bluff today, gazing at the Piasa’s menacing form, we’re reminded of its layered history. It’s a tale of Native American spirituality, European curiosity, and modern reinvention: a legend that, whether fact or fiction, continues to soar over the Mississippi, devouring not men, but our imaginations.

Leave a reply to William Perkins Cancel reply